Analysis of wildlife crimes data, supported by numerous interviews, finds evidence of systematic failure by Nigerian law enforcement and the judicial system to hold wildlife poachers/traffickers accountable.

This excellent report by Ini Ekott on the present status of wildlife crime investigation and prosecution within the criminal justice systems of Nigeria at the federal and state level, is a very clear indicator of the seriousness of the situation. (This report appears in the Premium Times Nigeria and Mongabay).

March 4th, 2022: After a poacher died following a clash with rangers at Nigeria’s Yankari Game Reserve, officials went with police to the nearby communities in Bauchi State, in the country’s restive northeast, to calm tensions. The relatives of the deceased had vowed retaliation.

In May 2013, about a month after the encounter, poachers ambushed a patrol team and shot a ranger dead. Weeks later, another ranger, left by colleagues to watch their motorbikes, was brutally hacked to death. Officials managed to arrest one of the killers, but they had a different concern: Even if all the assailants were caught, they were unlikely to face justice.

There were telling examples. Poachers arrested in the past returned to hunt in the reserve after being “allowed to escape from custody or (are) released after paying a very small fine only”, according to official records. One elephant poacher arrested three times returned after his court cases were abandoned each time.

Then in 2016, a man described as Yankari’s most wanted elephant hunter, who had killed a ranger before, was arrested after being on the run for years. But as the officials feared, the man, identified as Ilu Bello, regained his freedom just months after being handed to police. No explanation was given for his release.

“Prosecution of suspects arrested in the reserve is still very poor and the penalties imposed do not discourage offenders to stop or reduce poaching and illegal activities in the reserve,” the U.S.-headquartered Wildlife Conservation Society (WCS), which handles patrols at the reserve in partnership with the Bauchi government, wrote in its report in 2013.

In Cross River State, hundreds of kilometres south, poachers frequently raided animal sanctuaries too. And like in Bauchi, many of those caught were freed. All 15 hunters arrested in 2020 at the Afi Wildlife Sanctuary were reported to the Cross River State Forestry Commission for prosecution. None was charged.

“The lack of prosecutions is negatively affecting (the) morale of rangers who take great risks making arrests,” the WCS said of Afi.

At sea and air ports in Lagos and Port Harcourt, and at land borders in Adamawa and Katsina, traffickers of wildlife also escaped justice.

Nigeria has for years failed to hold wildlife traffickers and poachers accountable for their crimes despite federal and state laws that criminalise the killing and trading of protected species, an investigation by PREMIUM TIMES and Mongabay has found.

Our reporting revealed a trend: In many cases, wildlife poachers and traffickers were not arrested or traced; most of those caught were not prosecuted; and the few charged to court were asked to pay small fines or serve short terms. Many returned to their businesses after.

Suspects paid as low as N20,000 ($47) instead of a three-year jail term for killing an endangered animal such as chimpanzee or pangolin. Poachers were not arrested in multiple cases because there were no vehicles to convey them, and those arrested were later released because officials said there were no funds to keep them in pre-trial detention or pay lawyers for their trial.

At the ports, traffickers who ferried tens of thousands of tonnes of elephant tusks, rhino ivory and pangolin scales worth several millions of dollars were mostly never traced. Of 63 total interceptions collated between 2010 and 2021, suspects in 52 of the cases were either not arrested or charged to court. Many cases were listed to be under “investigation” for years.

No suspect, amongst them Nigerians, Chinese, Malians, Guineans, and Ivorians, served a jail term over the last decade for illicit trafficking of animals. The government said it obtained four convictions in the last 11 years – three were awarded small fines.

“It (convictions) is very low because we have to improve the capacity of our judiciary and our enforcement in understanding what wildlife crime is,” Nigeria’s Minister of State for Environment, Sharon Ikeazor, told us. “What are the endangered species? And what are the threatened species that should not be traded? It’s a lot of work we have to do.”

The findings are based on government and court records on seizures since 2010, publicly available data, and our analysis of hundreds of pages of reports of law enforcement at five wildlife reserves between 2012 and 2021.

After federal agencies initially refused to provide data, we obtained Nigeria’s submission to the Swiss-based Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES). The Nigeria Customs Service later released its record under the freedom of information law, and the National Environmental and Standards Agency (NESREA) provided additional information. The Federal Ministry of Environment’s Department of Forestry did not respond to our requests for data.

We also interviewed officials, including prosecutors, environmental campaigners and traders at wildlife markets in Lagos, Cross River, Ogun and Bauchi States as well as the Federal Capital Territory. Together, they shine a light on how Nigeria’s law enforcement and justice systems have done little over the years to deter perpetrators of wildlife crimes.

HUNTING GAME

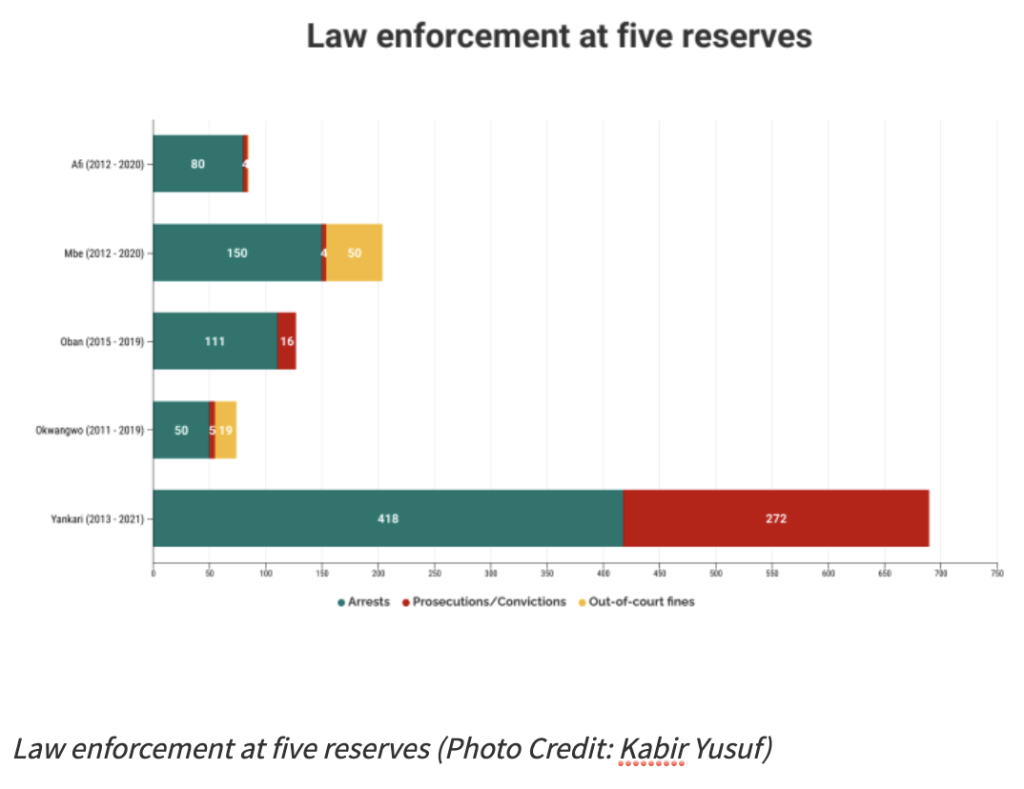

The law enforcement records cover four protected areas in Cross River, namely, Mbe (community-owned), Afi (state-owned), Oban and Okwangwo (federal government-owned); and one in Bauchi, namely, Yankari (state-owned).

Created in 1956, Yankari became Nigeria’s biggest national park in 1991. It was handed back to the Bauchi government in 2006. A top destination for tourists, the 2,244 square-kilometre sprawling reserve is home to the critically endangered West African lion, buffalo, hippopotamus, roan and hartebeest and the Nigerian savannah elephants.

It suffered major losses between 2006 and 2014 when neglect by the authorities allowed poachers, herders and farmers a free reign. During this period, many elephants were killed to supply the illegal ivory market. Government records say the population of the savannah elephants fell from 350 at the time to about 100 now.

Protection levels rose after the Bauchi government signed a co-management agreement with the Wildlife Conservation Society in 2014, and arrests spiked with rangers offered $15 (N6,200) for each poacher arrested and $80 for the arrest of an elephant poacher.

But weak prosecution and penalties ensured poaching remained a threat. Elephant killings were recorded in 2020 and 2021, the first time since 2015.

Between 2013 and 2021, Yankari recorded 418 arrests of poachers but only 272 were prosecuted, according to our analysis of the annual records filed by WCS.

The penalties were even weaker. In 2013 after several animals were found dead, including seven elephants with their tusks missing, hunters arrested that year received sentences of between six months to 18 months in jail.

They were, however, given the option of paying between just 10,000 ($63) and 160,000 naira as fines. A kilogramme of elephant tusk cost up to $2500 (410,000 naira at the time) in the black market in 2014, according to the Geneva-headquartered Global Initiative Against Transnational Organized Crime. An elephant’s two tusks can weigh up to 110 kilogrammes.

In 2017, hunters found to have killed hartebeest, hippos, baboon and patas monkeys were jailed between two and 18 months. They got fine alternatives as low as N30,000 ($189). Only repeat offenders had no option of fine.

Hunters arrested in 2020 for killing waterbucks, bushbucks and hartebeest, and suspected of killing an elephant and removing its tusks, got between six and 18 months in jail.

In a few cases, the reports say rangers took bribes from poachers and released them, afraid prosecutors and court officials would compromise the cases and release the suspects after all.

Some of the most tragic events at the reserve occurred in 2013. Rangers in April that year clashed with three poachers, and when one of them died in police custody, his family threatened retaliation.

Officials met with community leaders and received assurances there would be no reprisal. But on May 8, at about 11:30 p.m., poachers ambushed a patrol team and killed a ranger identified as Danazumi Baba. In June, another ranger, Babawuro Husseni, was attacked with machetes while his three colleagues left to survey their patrol area. They found his body some 100 meters away.

Rangers hunted for the assailants for months, while also trying to track the reserve’s most wanted elephant poacher, Mr Bello, who himself had also killed a ranger a year earlier. Mr Bello was finally arrested in 2016 by rangers and soldiers in the neighbouring Plateau State, but police released him just months later.

“We have not been told what happened, but we know he has been free,” said Nachamada Geoffrey, WCS’ landscape director for Yankari.

He said while security improved at the reserve over years, offenders still get away with weak penalties. “The Yankari protection law is outdated, and the penalties need strengthening to act as a deterrent,” he said. “If there are tough enough jail sentences to offenders as a deterrent, hunting and livestock pressure would be mitigated.”

Under the Yankari protection law, killing protected animals attract between three to 18 months in jail, with the option of fines. After years of failed promises, the government is now working to amend the laws, we learned. The state commissioner for environment, Ahmed Asmau, did not respond to requests for comments.

COMPOUNDING THE ISSUE

The four reserves in Cross River reported the arrest of 401 poachers, a collection of 59,091 wire snares and 16,879 spent cartridges used by hunters between 2012 and 2020, but they recorded only 19 prosecutions, seven convictions, and 70 out-of-court fine settlements.

The poorest instance of law enforcement involved the Afi Wildlife Sanctuary, where 80 arrests were made in nine years, and only three were prosecuted while one was convicted.

Two of those charged were caught with the bones of two gorillas. Afi, established in 2000, is home to an estimated 25 to 30 of the rare Cross River gorillas.

In many cases, suspects caught hunting were merely warned and released. Others could not be arrested because of “logistical reasons” as rangers had no vehicle to transport them.

At Mbe, of 160 arrests made in nine years, there were only two prosecutions and convictions. One offender was sentenced to one year in jail or N110,000 fine for killing a female chimpanzee, and another to three years or N20,000 fine for killing an unnamed endangered specie.

Fifty of those arrested were asked to pay fines between N2,000 and N20,000 to the host community, an out-of-court settlement called “compounding,” which allows officials to collect fines in place of prosecution. Experts say it breeds corruption and the fines are too small to deter offenders.

“Compoundment seems to be a preferred option for settling these cases, but it does not provide enough deterrence,” said Inaoyom Imong, WCS’s Cross River director. “Cases that get to court hardly get to the end due to compoundment, lack of political will, and lack of evidence.”

At Okwangwo, where at least three elephants were killed, 50 arrests were reported, and only five were prosecuted in nine years. Nineteen people were “compounded”. Hunting pressure in the area was shown by the number of wire snares and cartridges: 10,858 and 3,428. Many poachers were also not arrested because of lack of vehicles.

At Oban, between 2015 and 2019, there were 13 prosecutions out of 111 arrests of hunters. Five convictions were recorded, each jailed one year for killing pangolins, duikers, and monkeys.

Officials in Calabar, the Cross River capital, described how the CRSFC repeatedly cited lack of funds for releasing suspects. “The commission says it does not have funds to keep detainees and pay for legal fees of prosecuting them,” one official said, speaking on the condition of anonymity to discuss the issue freely.

The head of the commission, Anthony Undiendeye, said poor funding made law enforcement difficult. He also blamed manpower, high unemployment that makes locals fall back on the forest for livelihood.

“Poor law enforcement may make it seem as if the government technically supports it. We don’t,” Mr Undiandeye said. “My governor is a professor of environment and fully understands the implication of depleting our forest reserves. He decries it every day.”

He said things were better when the state operated a partial ban on the use of forest resources, which allowed communities to benefit in some ways. “Poverty has made people despondent, and livelihood is an aspect we need to address,” he said.

At the Aningeje Market, 51 kilometres from the Okwangwo reserves, where bush meat is sold, Mkpe Otu, a hunter who had arrived for the day’s sales, narrated how he sources animals from protected areas.

He said in the past, when authorities were more stringent going after poachers and loggers, hunters used more snares and wire traps. He said these days they hunt at night with dane guns when the rangers rarely show up.

The WCS admitted its patrols were mostly in the day due to logistics problems, and that the number of arrests did not give a true picture of the hunting and logging pressure on the reserves as most poachers operate at night.

A trader who buys dried pangolins, monkeys, and other species from Aningeje market and resells at the Big Quo area of Calabar, said traders were sometimes questioned by the state’s wildlife officials who visit markets to ask about their sources of pangolins.

The trade has continued nonetheless. Late January, she spread out a dried pangolin, monkey, and grass cutter at her stall and offered the pangolin for 4,000 naira and the monkey for 7,000 naira.

Conservationists say such sales, although mainly on a subsistence scale amidst high poverty levels, have taken a toll on Nigeria’s wildlife stock over the years. They have also fed a more extensive web of illicit wildlife trade, for which Nigeria has become a major global hub.

“When we go out we see pangolins, we see them at the roadside, and we are worried,” said Olajumoke Morenikeji, professor at the University of Ibadan, who leads the Pangolin Conservation Guild Nigeria.

BOOMING TRADE

Global illicit wildlife trade has grown rapidly in the last decade, pushing some species close to extinction. The World Bank estimates the trade at $7.8 billion to $10 billion a year, making wildlife crime the fourth most lucrative illegal business after narcotics, human trafficking, and weapons.

The Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES), hosted by the United Nations Environment Programme, brings together 179 nations to combat illegal wildlife trade through uniform regulation. As a CITES signatory, Nigeria outlaws the killing of endangered species or animals in protected areas and illicit trafficking of animals.

Yet, Nigeria has emerged as a top source and transit country for illicit trade in ivory and pangolin scales, with smugglers attracted by its porous borders, corruption level, transport links to Asia, and poor law enforcement.

Between 2009 and 2017, Nigeria was linked to 29.6 tonnes of seized ivory globally, and in 2019 at least 51 tonnes of pangolin scales seized anywhere originated from the country, according to the United Nations Office on Drug and Crime, UNODC.

Nigeria made its single largest seizure of pangolin scales on its soil in January 2020 when officials seized 9.5 tonnes of the anteater’s scales worth an estimated N10.6 billion ($25.9 million).

In 2021 alone, the Nigeria Customs Service intercepted 18.69 tonnes of elephant tusks, rhino horns, pangolin scales, and claws at various exit points across the country, according to our compilation. Just this month, it seized 145 kilograms of elephant tusks and 839.4 kilograms of pangolin scales at the upmarket Lekki district of Lagos.

Such seizures, typically displayed before journalists, are usually seen as a measure of success against traffickers, and not much is heard about the cases afterward.

Our review of government records and interviews with officials showed that despite the huge seizures over the last decade, no one served a jail term. Of 63 interceptions we collated between 2010 to 2021, only 11 cases went to court; many never concluded. No arrests were made in most cases.

The three convictions the government said it got, all between 2012 and 2013, involved Chinese nationals caught with 5.4 kilogrammes of processed ivory. They were asked to pay just N100,000 ($629) as fine in place of a three-year jail term. Under Nigeria’s Endangered Species Act, fines could reach N5 million.

Interestingly, another Chinese arrested the same period with a smaller quantity of processed ivory was made to pay N5 million in an out-of-court settlement. — the highest fine by any offender.

We found that authorities in most cases do not go after the actual owners of seized shipments even when there are clues. Also, three years after the government promised to investigate how over 34 shipments intercepted outside the country left its shores, we found no evidence that has been done.

In acknowledging that most cases were not taken to court, the National Environment Standards and Regulations Enforcement Agency (NESREA), the lead law enforcement agency on wildlife offences, said some cases were settled out of court through the payment of administrative fines while others involved items “abandoned” at ports with no owner in sight.

“Most of the suspects you see on those cases are usually abandoned consignments,” the director-general of NESREA, Aliyu Jauro, told us. “When they are about to be caught, they leave it and run away, so at the end of the day, the Nigeria Customs Service will just come to NESREA and say we have this specimen with us, or they will just hand it over to us. So when you don’t have any person to prosecute, what do you do?”

A spokesperson for the Customs Service, which also has the powers to prosecute wildlife smugglers, said after cases go to court, the agency has little control over the outcome or pace of the judicial process.

“The issue of justice is not entirely in the hands of customs,” said Joseph Attah. “At the time cases are handled by the courts, there is just little we can tell because we do not have the inner workings of the court, apart from the fact that ours is to ensure that we continue to make appearances whenever we are supposed to. The duration is not in our place to decide.”

However, a recent case shows that while judicial delays might contribute to poor justice delivery, government agencies like Customs do not do enough to investigate, arrest, and prosecute offenders.

LEADS UNFOLLOWED

The January 21, 2021 haul of pangolin parts, the second-largest seized by Nigerian authorities ever, arrived at the Apapa port in Lagos deceptively packaged.

On paper, the 20-feet container prepared for export to Haiphong, Vietnam, contained furniture but inside officials found woodwork used to conceal 162 sacks of pangolin scales and claws weighing 8.8 tonnes. They also found 57 bags of elephant ivory and lion bones.

At an event announcing the seizure, Mohammed Abba-Kura, a Customs comptroller, told journalists of the agency’s resolve to combat wildlife smuggling and assured the organisation would act after its investigations.

More than a year after the announcement and several months after Customs completed its investigations, the case has not moved forward in court – evidently due to the handling of the case.

Court records show that Customs filed its affidavit of completion of investigation at the federal high court in Lagos on June 28, 2021, but as of the publication of this story, it has not arraigned any suspect on the matter.

We found that operatives arrested only the forwarding agent who processed the shipment as they did not go after the real owners of the cargo. Felix Olame, shown to the media in January 2021, was later released on administrative bail.

His arraignment was initially delayed due to the investigation by the agency and also by a strike by judicial workers in April 2021. After court activities resumed in June, Customs’ lawyers filed the case in court, but did not arraign Mr Olame as he had not been re-arrested.

Records show the matter was adjourned to December to give time for the accused to be brought for arraignment, and the court issued a bench warrant for the suspect to be “brought from detention” for arraignment. That did not happen as the accused was not re-arrested.

The case was again adjourned to January 27, 2022. Again, the matter was suspended as the accused was still not in court, prompting another adjournment.

We also found that investigators did not act on tips to go after the actual cargo owners by examining their phone numbers and company details, available on the export forms, with phone companies and the Corporate Affairs Commission. Court filings make no reference to the owners of the shipment.

“This shouldn’t be a difficult thing. Their phone numbers are there, and their company registration can be found,” one government official said on the condition of anonymity to discuss the matter.

Officials interviewed alluded to “big money” in the business that sometimes makes it difficult for law enforcement officials to follow through the process.

“These types of cases require those involved to be able to resist a lot of temptation. Because we know a lot of money is involved,” another official said.

Another official said the likely outcome of repeated adjournments of the case is for the court to dismiss the case for lack of diligent prosecution.

Within Customs’ bureaucracy, the responsibility to arrest and present the suspect in court lies with the agency’s enforcement unit, which we confirmed received notification to act. Reached by phone, the head of the department at Apapa, Haruna Nasir, said he could not comment on the matter.

NOT TOGETHER

Under the government’s procedure, suspects arrested for violating federal wildlife laws are to be handed over to NESREA for prosecution. However, other law enforcement agencies can prosecute offenders.

The Customs Service can charge wildlife trade suspects under its law prohibiting export of banned items, and the anti-graft body Economic and Financial Crimes Commission (EFCC) can prosecute traffickers for possessing or exporting proceeds of crime under its money-laundering laws.

In all, more than 20 agencies are involved in the effort to combat illicit trafficking of wildlife products, but the burden of seizing wildlife shipments and those behind them in reality falls more on Customs as the primary agency at land, sea and air ports.

Given the number of agencies involved, the UNODC says cooperation is key to achieving success.

“Bringing everyone together in this business is really absolutely critical,” said Olive Stolpe, UNODC representative to Nigeria.

That cooperation is currently lacking between NESREA and Customs. It is first seen in the figures released by the two bodies. While NESREA reports three cases of interceptions between 2019 and 2021, Customs reports 24.

Customs stopped reporting its seizures to NESREA in 2018, according to records, and since then collaboration between both agencies on wildlife cases has not improved. NESREA said it has repeatedly been left in the dark about issues.

“What is happening (in NESREA) is that we are not at the borders, rather (it is) the Nigerian Customs. The arrangement is whenever there are such cases, they will call us, they will hand over the wildlife specimen and suspects to us to prosecute. For a very long time, they have not been calling us,” NESREA director-general, Mr Jauro, said.

“Sometimes, over the news, we get the information that they have made arrests, seizures and they just go there and announce it. That’s it; we don’t have any information. We are trying to see how we can sit down with them to collaborate just like we were doing before.”

Customs started directly prosecuting cases of wildlife interceptions in 2019, but like NESREA, its record of prosecution is abysmal.

The agency has only three cases in court out of 24 total seizures between 2019 and 2021. It said one case was completed but did not give details of the sentence.

All Customs’ 14 seizures recorded in 2019, except one, remain under “investigation” more than three years after, with none progressing to the court.

LITTLE CHANGE AT WILDLIFE MARKETS

The tepid wildlife law enforcement and justice has meant that the more things appear to change, the more they remain the same.

Kingsley Peter (not his real name), an art trader at the Lekki craft market in Lagos, remembers the day an Asian-looking man showed up at his shop.

Foreign nationals regularly visited the popular market, a mishmash of complex wooden stalls at the backwaters of Lekki, where arrays of art items made from every imaginable material, from wood to ivory to crocodile skin, were sold.

The site was also a meeting point of sorts for operators in the illegal wildlife sector, who occasionally called in to forage for raw animal parts.

Mr Peter, a middle-aged man, said the customer asked if he had a tusk. The artist said he showed a tiny bull horn he had reworked to appear more like a piece of a tusk, although he said a careful examination would still reveal the difference.

“He quickly snatched it and hid it so others won’t see. He didn’t even look at it carefully, he offered to pay,” said Mr Peter.

That was before 2018 when the market boomed and foreign clients openly patronised wildlife dealers. Things changed after Customs and other operatives raided the market in 2018. But not much has changed.

The market continues to operate, although most of its foreign clients – Chinese, Malians, Guineans, etc. – have stayed away. Raw animal parts, shipped in from outside the country, are no longer traded openly as before, but the processed ones remain on the shelves of shops there. Deals are still cut behind the scenes, traders said.

During a visit in December 2021, the market was expectedly not as busy. With few customers around, some sellers of carvings, some made from banned wood, reclined into an early afternoon nap.

We saw carved elephant ivory on display for sale – an illegal trade the government acknowledges exists but has failed to stop.

“Those behind the sales, some who shipped them in from Cameroon and other countries that time, are still around,” Mr Peter said. “They were never arrested.”

Mr Peter and other traders said with a serious offer, dealers can bring in ivory or pangolins. Officials have not conducted a raid there for years, the traders said.

A similar market continues to operate in Abuja, the capital. We saw processed elephant ivory products sold openly at the Abuja craft market.

Asked about the Lekki market, which the government has repeatedly pledged to close or at least regulate its activities, the head of NESREA, Mr Jauro, said the agency was not aware the market was still operating. He promised action.

At the Epe bush-meat market, a seaside square set on aging wooden frames some 74 kilometres from the Lagos mainland, a man who gave his name as Kunle, who has been involved in wildlife sales, also offered to source pangolins.

He displayed a live pangolin and alligator during a recent visit and showed several of the animals on his phone sold in the past days. He offered the live pangolin for 20,000 naira.

“This is what I’ve been doing for years, and they know me,” he said.

Kunle said he travels to other parts of the country to bring in supplies.

He said authorities have shown more interest in stopping the business lately but said that did not stop them. The open display of live pangolin at the time of visiting in the afternoon confirmed that. More supplies had come in the morning, traders there said.

“If you are serious, it’s just to deposit money, and we will get up to 20 pangolins in weeks,” Kunle said.

CORRUPTION, WEAK LAWS

Experts point to several reasons Nigeria is unable to combat wildlife crimes. First, officials do not see it as a major problem. A 2019 assessment by the Federal Ministry of Environment said wildlife trafficking was not a priority for Customs officers at the seaport and that “their focus is mainly on revenue, narcotics, and weapons trafficking.”

With that, there is an evident lack of interest in prosecuting cases.

“Yes, the laws are weak – but the level of awareness amongst law enforcement officials is embarrassingly low,” said Adedayo Memudu of the Nigerian Conservation Foundation, the country’s oldest conservation-focused non-governmental organisation.

Corruption also ensures banned animal parts are still easily moved through the country, and suspects are either not tried or are given a slap on the wrist.

At the Epe and Lekki Arts markets, traders brushed off concerns about how mock orders for pangolins we placed would be ferried to Lagos through security checkpoints across the country. “That is not a problem. We can take care of that,” one said.

The 2019 assessment by the environment ministry concluded that “As at (with) the Murtala Muhammed International Airport, the level of corruption appears to be very high at the seaport and is an obstacle to wildlife law enforcement,” referring to the Lagos airport and seaport.

There is also the problem of weak laws. The main law operated by NESREA against wildlife crimes, the Protection of Endangered Species in International Trade Regulation 2011, can punish illicit trafficking up to N5 million fine and/or three years in prison. No one has served any such sentence.

To compare, a Malawian court in 2021 punished a Chinese trafficker with a 14-year jail term. A Cameroonian court in 2017 imposed a half a million dollar fine on two convicts found guilty of trafficking 159 elephant tusks.

“They are not sufficiently deterrent and allow for compounding probably because wildlife crime until possibly the last couple of years was not perceived as a serious criminal offense,” said Foluso Adelekan, National Programme Officer, UNODC’s Wildlife & Forestry Crime Project.

The National Park Services Act 1999 punishes hunting an endangered, protected, or prohibited species or hunting a mother of a young animal or large mammal species in a national park with three months to five years, with no option of fine.

The use of a snare is punished with between ₦10,000 and N50,000 fine, attracts one to five years in jail, while using a firearm, spear, bow, poison, explosive receives between ₦5,000 and 25,000 and/or six months to five years.

The penalties are worse at the state level. Killing an elephant in Ogun State, for instance, attracts 500 naira (about $1.2) in the state’s outdated law.

“The laws are very weak and very old. There have been efforts to bring them up to international standards,” said Mr Memuda. Attempts to review the state’s wildlife law has been unsuccessful for years as state lawmakers have yet to pass proposed amendments.

“We have to declare a statement of emergency not just on our reserves but our entire wildlife resources, otherwise we will not have anything left for the future generation,” he said.

For trafficking, the Customs law and the EFCC law present a relatively stronger provision than NESREA’s. While exporting or importing banned items attracts five years in jail without fine under Customs’ statutes, it draws seven to 14 years in jail under the EFCC’s anti-money laundering law.

The UNODC in 2020 began training Nigerian prosecutors and judges, and helping to coordinate efforts by Nigeria’s federal and state agencies to check wildlife crimes. Funded by the German government, the project has also supported the development of Nigeria’s first national strategy to combat wildlife and forest Crime, expected to be launched in the first quarter of 2022.

At an event in November 2021 to discuss the 45-page draft of the strategy paper, attended by the environment minister and heads of agencies, officials contested a touchy subject as stated in the document.

Drafters of the document, which when completed will be unveiled by President Muhammadu Buhari, said corruption has allowed illicit wildlife trade thrive in the country, but some officials disagreed.

The director-general of Forestry Research Institute of Nigeria, Adesola Adepoju, argued it made no sense for the country to give itself a bad review in a document international partners will review. He said the claim about corruption was not a reality.

He cited an example of how foreign partners had once claimed that confiscated animal parts in the custody of the Nigeria Customs had been stolen. “When we got to Customs’ warehouse, everything was intact,” he said. “So we need to be careful.”

But other officials insisted corruption remained a problem and should be highlighted in the document.

Mrs Morenikeji at the University of Ibadan said Nigeria must do more to tackle wildlife crimes and ensure the real culprits are caught and punished.

“There are real men, real dealers at the top of the chain; nothing is being done to those people. They have not been found out or brought to book,” she said.

Oge Udegbunam contributed research to this investigation.

This report is part of a series on environmental crime in Africa, supported by the Global Initiative Against Transnational Organized Crime, the Henry Nxumalo Foundation, and Oxpeckers Investigative Environmental Journalism.