‘Super-tuskers’ killed by trophy hunters in Tanzania

A 30-year-old deal to protect Kenya’s prized bull elephants appears to have broken down, with tragic consequences for the animals that cross an unmarked border

Jane Flanagan, Africa Correspondent

March 6 2024, The Times

The heaviest elephant tusks on record are held at the British Museum and had a combined weight of 465lb when they were taken from a hunt in 1897 on the lower slopes of Mount Kilimanjaro.

Like lumbering relics of a bygone era, the descendants of that male have remained in the area on Kenya’s border with Tanzania. Known as the “super-tuskers” for their ivory that sweeps the ground, each weighing more than 100lb (45kg), the bulls are the most studied and photographed elephants in Africa.

Like their ancestor, though, their extraordinary tusks put them at risk, perhaps even more so since their numbers have dwindled to only a few dozen. Three of the super-tuskers from the Amboseli National Park have been killed since September on the Tanzanian side of the border, where hunting is still legal and trophy hunters are willing to pay up to $300,000 to bag a bull. The most recent was last week and conservationists fear the hunt is part of a trend to get bragging rights to a “100 pounder” before they disappear for ever.

“These elephants will let you get a few metres away. They are very tame around people,” said Joyce Poole, an academic who has researched the population since the 1980s. “Killing them is hardly a sport.”

News of the hunts have emerged in local reports and included unsettling details. At least two of the carcasses were burnt after the hunts which took place in September, November and last week. Such a practice is not usual in Tanzania and meant the animals’ unique identifying features were lost.

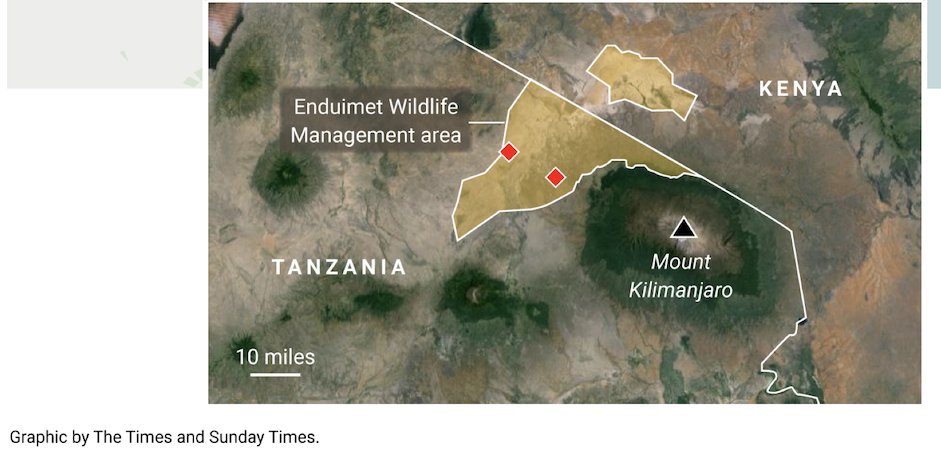

The hunt in November was preceded by a helicopter flying extensively over the Enduimet Wildlife Management Area, in the foothills of Mount Kilimanjaro, Tanzania. Though considered unethical, aircraft are sometimes used to spot animals and harass them into moving into an area where hunting is permitted — such as in a designated concession of Enduimet just a few miles from Kenya, where hunting has been banned for decades. There are no fences to block the animals’ path.

An agreement between the neighbours that no hunting should take place on the border has held for 30 years, since three well-known Amboseli elephants were slaughtered in 1994. The deal was respected until now.

Although African elephants are listed as endangered, not all are protected against hunting under the international agreement known as Cites to control international trade in endangered species.

Tanzania’s operators frequently boast that they offer some of Africa’s best hunting experiences. The Times contacted Kilombero North Safaris, which has the concession to operate hunts in the area where the three elephants killed since September are believed to have been targeted. A staff member said its directors were “travelling” and would respond to questions about the hunts “in due time”.

Local reports have linked the company to the September hunt and the one last week, news of which coincided with a social media post by the prolific American hunter Rick Warren in which he thanked Kilombero North for a recent trip. Warren opened a gallery in his native Austin, Texas, of stuffed animals he has hunted on dozens of trips to Africa. In a post shared on Instagram this week he was photographed next to a dead kudu at Mount Kilimanjaro.

On its Instagram account, Kilombero North posted a picture in June of a client posing between the vast tusks of a dead elephant. A separate image shows one of its staff holding yellowing ivory that, the caption said, evoked the “sense of Old Africa”. It added: “Times have certainly changed but for the hunter willing to put in the miles there are still phenomenal elephant areas and there’s still big ivory out there if you know where to look.”

Supporters of regulated trophy hunting argue that it helps to manage wildlife populations and provides an income to communities, and incentivises them to protect animals from poaching and farming.

Conservationists counter that trophy hunters typically pay to kill animals which are in their prime: the adult male elephants being killed in northern Tanzania, for example, play a key role in reproducing and maintaining social order in their populations.

Camera protection

The Indian state of Kerala will install 250 cameras along the fringes of its forests to protect residents from deadly elephant attacks (Amrit Dhillon writes).

This year seven people have been trampled to death on the roads and fields around the forests where 2,000 elephants live. Last year 17 people died in such attacks.

Sensory alarms and drones are being used to track elephant movements and alert residents.

This week a women, aged 62, was killed while working in the fields. Another, aged 70, was killed in a rubber plantation. There were protests in the hill station of Munnar last week after an elephant killed an auto rickshaw driver taking passengers home.