Has Poaching Increased or Decreased in Africa?

On Friday July 10th, 2020, the UNODC (United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime) presented the 2020 Wildlife Crime Report in what was described by CITES as “a high level virtual event”.

For those who don’t know, the UNODC is an office within the United Nations and has about 500 staff working in 20 field offices around the world. They work in educating people about crime and crime prevention, assist with criminal justice reform and combatting transnational organized crime and corruption. They also publish a lot of reports; on drugs, violent crime, financial crime, and even include prisons in their studies.

This particular report is the second major report relating to wildlife crime, the previous one completed in 2016. It is 136 pages long and replete with the expected pie charts and graphs.

Having said that, if someone who had absolutely no knowledge of wildlife crime read this report, they would walk away with a pretty good idea what it is all about. There are contributions from many agencies and persons who have recognized credentials and hands on experience and knowledge.

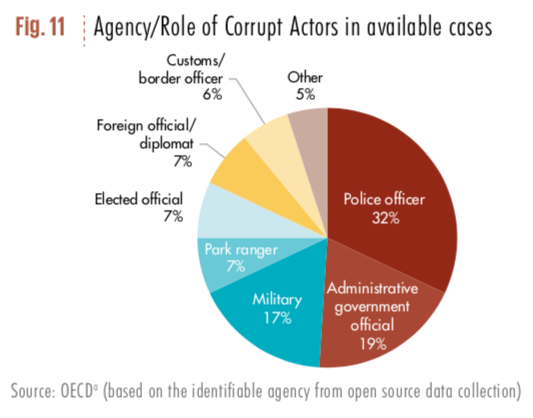

Corruption is even discussed beyond the typical lip service often seen in this type of report.

There is a flaw, however, the degree of seriousness yet to be determined.

You see, this report is based primarily on data. And the data that it is based on is at least 2 years old. The authors recognized that and it is mentioned severally though out the report.

To complicate this further, some data is made from assumptions (sometimes referred to as ‘suggested evidence’) and some assumptions are based on data that may or may not be accurate. The number of elephants remaining on the planet, the number that are being poached, the amount of ivory seized and the number of seizures made are all areas that are anything but cut and dried.

There is a lot of information in this report and a great number of media outlets picked up the story. Two headlines were predominant. One along the lines of “Wildlife Crime Putting Environment and Health at Risk” and the second headline indicating that there has been a decline in elephant poaching and trafficking.

And herein lies the problem. Is there really a decline in elephant poaching and trafficking?

On June 23rd, 18 days before the launch of this report, ‘Scientific Reports’ published a peer reviewed article written by five well known and respected scientists (3 of the authors are cited more than once in the 2020 report), indicating the opposite of what was headlined in the UNODC press release.

The essence of the Scientific Reports study is that contrary to popular belief, since 2011, there has been a decrease in only East Africa and that poaching rates in South, West and Central Africa have essentially not changed. This is far from the “illegal ivory trade shrinking”.

Not surprisingly, the Scientific Reports publication did not receive the same attention as the UNODC report so millions of people, perhaps hundreds of millions of people who scan headlines from the likes of Reuters or the New York Times, now believe that the illegal ivory trade has diminished. Even the CITES website made similar mention when at best the UNODC 2020 report is “premature and misleading” as quoted by the Environmental Investigation Agency (EIA), or completely wrong.

The “high level virtual event” was showcased with speakers from UNODC, CITES and the EU and some of their quotes included: “accurate data is the bedrock of policy making”, the report is “rooted in the best data available” and the report “provides governments with a clear picture of the situation.” Unfortunately now, in reality, the picture is anything but clear.

Being gracious to UNODC, I am sure there was no time to change their report even if they had wanted to. That report was at least 2 years in the making and would have required a lot of approvals before being published. But could they have held off? Or could they have made mention of the recent data that conflicted with theirs.

The implications are all negative. Millions of dollars could be re-allocated away from anti-poaching initiatives. Some countries may use the numbers to bolster their argument for opening up the sale of government stockpiles. Some countries may use the report to further the perception that they have a handle on poaching/trafficking when, in fact, they don’t. Far East markets may increase because buyers now think the elephant poaching crisis is over.

And a distinct possibility: more elephants die through a UNODC report that was supposed to achieve the opposite.